Research

My research has four connected themes.

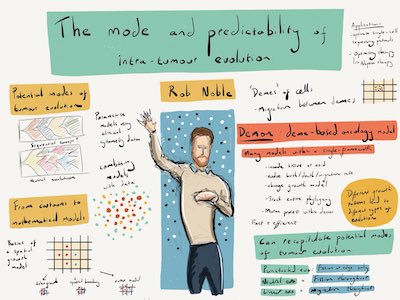

Dynamics of somatic evolution

The proximate cause of cancer is somatic evolution. Recent studies have unveiled extensive genetic heterogeneity not only in tumours but also in normal human tissues. Yet while rich data sets are rapidly accumulating, we still have little understanding of the evolutionary processes that generate the observed patterns of diversity. Characterizing somatic evolution is fundamentally important for cancer prevention, early detection, and effective treatment.

I have created a sophisticated spatial computational model of tumour population genetics that can simulate a range of tissue architectures within a common mathematical framework [1]. By parametrizing this model using information derived from histopathological image analysis, I have shown that differences in tumour architecture can explain the variety of evolutionary modes observed in human cancers, including four archetypes [2]. In close collaboration with laboratory biologists, I have further investigated ecological interactions between cancer clones including facultative parasitism mediated by paracrine factors [3]. I have developed new methods for comparing and classifying evolutionary modes, and more generally for describing the shape of any rooted tree [4,5,6].

I am extending my modelling framework towards a general systematic understanding of somatic evolution. To test predictions and refine research questions, I will continue to use molecular data, in collaboration with bioinformaticians, experts in histopathological image analysis, and specialists in multi-region sequencing of tumours and heathy tissue.

Collaborators include Jakob Kather (RWTH University Hospital, Aachen) and Darryl Shibata (USC, Los Angeles).

References:

- Bak et al. Warlock: an automated computational workflow for simulating spatially structured tumour evolution. arXiv (2023)

- Noble et al. Spatial structure governs the mode of tumour evolution. Nat. Ecol. Evol. (2021)

- Noble et al. Paracrine behaviors arbitrate parasite-like interactions between tumor subclones. Front. Ecol. Evol. (2021)

- Lemant et al. Robust, universal tree balance indices. Syst. Biol. (2022)

- Noble & Verity. A new universal system of tree shape indices. bioRxiv (2023)

- Manojlović et al. Expected and minimal values of a universal tree balance index arXiv (2025)

Forecasting tumour evolution

Accurate methods for predicting whether neoplasms will grow aggressively, how they will initially respond to treatment, and whether and when drug resistance will develop, are lacking. Computational models that account for cancer’s dynamic, evolving nature have enormous, untapped potential to provide more detailed patient-specific forecasts for informing clinical decision making.

Working closely with clinical and experimental oncologists during a four-year clinical trial, I have developed and analyzed a mathematical model of clonal dynamics during interferon-alpha treatment of myeloproliferative neoplasms. By combining my dynamical model with a sophisticated Bayesian inferential method, we have obtained the first estimates of mutated-cell proliferation and differentiation rates in these diseases [1]. In the more challenging case of solid tumours, I have used computational modelling to assess when, why and how intratumour heterogeneity can be used to forecast tumour growth rate and clinical progression [2]. I have further shown how my new approaches to quantifying the shape of evolutionary trees provide new ways of forecasting clinical outcomes [4]. This work together informs the search for new prognostic biomarkers and contributes to establishing a theoretical foundation for the new field of predictive oncology.

I am now working towards models that can forecast the evolution of realistically large, heterogeneous tumours. This includes using diffusion approximations and other methods from statistical physics and population genetics to describe how clonal expansion speeds depend on key biological parameters [3], and using machine-learning methods to infer patient-specific parameter values from clinical data.

Collaborators include Isabelle Plo and William Vainchenker (Institut Gustav Roussy, Paris).

References:

- Mosca, Hermange, Tisserand & Noble et al. Inferring the dynamic of mutated hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells induced by IFNα in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood (2021)

- Noble, Burley, Le Sueur & Hochberg. When, why and how tumour clonal diversity predicts survival. Evol. Appl. (2020)

- Stein, Kizhuttil, Bak & Noble. Selective sweep probabilities in spatially expanding populations. bioRxiv (2023)

- Verity & Noble. Evolutionary tree balance predicts disease-free survival in the TRACERx non-small cell lung cancer cohort. medRxiv (2025)

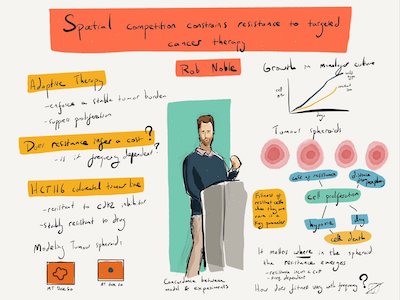

Evolutionarily-informed cancer therapy

Evolutionary theory and growing empirical data suggest that the emergence of resistance to cancer therapy may be prevented or delayed by exploiting competition between drug-sensitive and resistant cells. However, proposed mathematical models of evolutionary cancer therapies lack specificity. There is no reliable way to predict which strategy will work best for a particular patient.

In collaboration with cancer cell biologists using 3D tumour spheroid models, I have validated an adaptive therapy concept by using computational and mathematical modelling to show how spatial constraints can be exploited to suppress resistance to targeted therapy [1]. I have further contributed to extending these results towards mathematically rigorous theories of cancer adaptive therapy [2] and multi-strike therapy (also known as extinction therapy) [3] that unify and generalizes previous formulations. I have relatedly investigated how public goods cooperation in bacteria depends on ecological antagonisms [4], with potential implications for therapeutic manipulation of ecological interactions, such as in tumours that depend on paracrine growth factors.

Building on these results, I am investigating how different tumour architectures and microenvironmental feedbacks result in different optimal strategies. My long-term objective is to design optimal treatment regimens for each tumour type, and ultimately each patient.

Collaborators include Daniel Fisher (IGMM, Montpellier) and Yannick Viossat (Université Paris Dauphine, Paris).

References:

- Bacevic & Noble et al. Spatial competition constrains resistance to targeted cancer therapy. Nat. Commun. (2017)

- Viossat & Noble. A theoretical analysis of tumour containment. Nat. Ecol. Evol. (2021)

- Patil, Ahmed, Viossat & Noble. Preventing evolutionary rescue in cancer using two-strike therapy. Genetics (2025)

- Vasse & Noble et al. Antibiotic stress selects against cooperation in the pathogenic bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PNAS (2017)

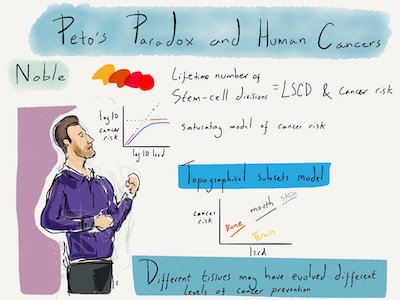

Evolution of cancer risk

The ultimate cause of cancer is that multicellular organisms have evolved imperfect defence mechanisms against the breakdown of cell-cell cooperation. This vulnerability can be understood through mathematical modelling in the framework of life history theory.

I have argued that most modern-day cancers in animals – and humans in particular – are due to environmental changes outpacing cancer resistance evolution. A more specific hypothesis consistent with available data is that combined risks of all cancers in a population beyond 5% can be explained by the influence of novel environments [1]. At the within-organism level, I have shown that variation in risk of human cancer types is analogous to the paradoxical lack of variation in cancer incidence among animal species and may likewise be understood as a result of natural selection [2]. My analyses indicate that differences in microenvironment, tissue structure and evolved protection mechanisms are of central importance in determining cancer risk [3].

Having shown that cancer risk per stem cell division is several orders of magnitude greater in some human tissues than in others, I am now working towards explaining this enormous variation by integrating demographic models with multistage models of carcinogenesis. This includes examining how systemic and tissue-specific cancer protection evolves subject to life history trade-offs across dissimilar tissues.

Collaborators include Hanna Kokko (University of Zurich).

References:

- Hochberg & Noble. A framework for how environment contributes to cancer risk. Ecology Letters (2017)

- Noble, Kaltz & Hochberg. Peto’s paradox and human cancers. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B (2015)

- Noble et al. Overestimating the Role of Environment in Cancers. Cancer Prev. Res. (2016)